Tajiki identity caught between Iran, Islam, and Russia

D Gershon Lewental, DGLnotes, 11 May 2014

Tajiki one-hundred somoni note depicting the Sāmānid ruler Esmāʿīl, emphasising the connexion between modern Tajikistan and the Ninth/Tenth-Century state.

[1]

The Republic of Tajikistan came into being in late 1991 as a state with no historical precedent. Emerging from decades of secular Soviet political and cultural control, cut off from the Tajik heartland of Bukhōrō and Samarqand, and facing a potent challenge from a charismatic Islamist movement, the country faces a great need to construct a cohesive and durable national identity. Several options were and are available to the leaders of the country: an embrace of Iranian ethnic roots, a return to the Islamic tradition that had defined the region in in the pre-Soviet era, or a continuation of the pattern of Soviet society and civil religion. While any one may appear a logical choice, each path brings with it certain hazards. This article discusses these various identities available to the Tajik leadership and how the country has navigated a careful balance between them.

This article is a summary of a paper, ‘Iranian and Islamic heritage and the formation of Tajiki national identity’, presented at the conference, ‘After the Persianate: Cultural heritage and national transformation in modern Iran and India’, organised by the Iranian Studies Program, College of International Studies, University of Oklahoma, 07–08 March 2014, Norman, Oklahoma. I thank Sitora Usmonova Lewental for her assistance in carrying out fieldwork and for her input on this paper.

Table of contents

1. The Need for a new identity

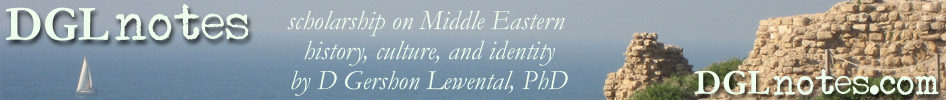

Map of mediæval trade routes in Central Asia.

[2]

The establishment of a Tajikistan during the Twentieth Century necessitated the creation of a concomitant ‘Tajiki identity’ and, eventually, ‘Tajiki nationalism’. Most cases of nationalism involved a large amount of ‘imagining’—and an even greater quantity was required in this instance. Although evidence can be found for the use of the term ‘Tajik’ to describe Iranian-language speakers,

1 historically, the term made no firm distinction between the local Iranian population and the Turkic peoples who gradually migrated and settled in the region. Broadly speaking, the population of Central Asia perceived differences not in terms of ethnicity or language, but in terms of way of life, and ‘Tajik’ became a description for the settled population of the region.

2 It is important to stress that the mingling of populations, languages, and cultures meant that the meanings of various terms were in constant flux and that none of them held historically any national or ethnic associations.

The leadership of newly-independent Tajikistan faced the challenge of defining its identity and distinguishing itself from the surrounding Turkic states. In the absence of an historical precedent for national existence, it was critical to justify Tajik existence, while coping with the loss of its cultural heartland of Bukhōrō and Samarqand. Ultimately, the new state had to establish its roots through unique referents of identity.3 In charting the course for the development of a national identity, Tajikistan encountered three different routes, each with its own advantages and disadvantages: (1) embracing its Iranian ethnic roots, (2) returning to and reviving the Islamic tradition, or (3) maintaining the pattern of Soviet society and secular civil religion.

2. The Iran option

Presidents Maḥmūd Aḥmadī-nezhād, Emōm-ʿAlī Raḥmōn, and Ḥāmid Karzay of Iran, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan meeting in Kuwait, 2012.

[3]

While any one may appear a logical choice, each path brings with it certain hazards. Although Tajikistan defined the Tajiki dialect of Persian as its national language and immediately established diplomatic relations with Iran (the first country to establish an embassy in Dushanbe), the secular leaders are wary of the Islamic Republic’s religio-political agenda and even the small religious class, as Sunnī Muslims, does not relate to Iran’s overtly Shīʿī identity. Thus, Tajikistan’s leaders focused extensively on the Sāmānid period, which served their interests well for promoting an Iranian discourse of a Central Asian flavour and Sunnī distinction. Furthermore, Tajiks are concerned about potential irredentist threats from Iran and have emphasised their own superiority in response to perceived Iranian condescension. As a result, the state has emphasised the Zoroastrian legacy of pre-Islamic Iran in order to underscore its dissimilarity from Shīʿī Iran, while also promoting what some have termed the ‘Aryan myth’—namely that Tajikistan is the ancient homeland of the Aryans or Indo-Europeans.

4

3. The Return to Islam

Tajiks praying in the central mosque of Dushanbe, 2010.

[4]

The Islamic tradition, too, has not been without its challenges. Since, 90 per cent of the population is Muslim, Islam seemed like a way to unify the country’s population, bridging the gap between the Tajik majority and the Uzbek minority (estimated at about 15 per cent). However, the political establishment views with grave concern the threat posed by radical Islamist elements to the stability of the state; the lessons of the bloody civil war, fought between secular former-Soviet élites and a coalition of opponents, in which Islamists played a prominent rôle, have not been forgotten. Moreover, the transnational nature of many of these groups undermines the agenda of the new country seeking to define itself in national terms. The state thus cultivates vague, superficial aspects of Islamic tradition, often associated closely with Central Asian culture.

4. Staying the Soviet course

Presidents Vladimir Putin and Emōm-ʿAlī Raḥmōn of Russia and Tajikistan, in a meeting in Moscow, 2013.

[5]

Ultimately, the neo-Soviet élite has found it convenient to maintain the existing model of political and social life, while injecting into it elements of the other two cultural models. This path offered the state several immediate advantages, including an existing familiarity with Russian language and culture, the continued hold on power by former-Soviet authorities, and the geopolitics of Central Asia within the Russian orbit. Tajikistan also finds itself dependent upon Russia in political, military, and economic terms. Furthermore, a large part of the population looks back on the Soviet era with nostalgia, associating the period with stability, development, and progress. The downsides to the Soviet approach—in particular, the reinforcement of cultural inferiority and lack of diplomatic independence—have been judged less dangerous to the new state than those of the other options, Iran and Islam.

5. Conclusion: Challenges and opportunities

The subtle dialogue between these three legacies reveals much about the development of a new national identity on the borderlands and crossroads of the Iranian, Islamic, and Russian cultural zones. Tajikistan has navigated a careful balance between the powerful tugs from Iran, Islam, and Russia, while focusing on the influence and appreciation of Iranian and Islamic heritage in contemporary Tajikistan on the historical/political, cultural/literary, and social/religious planes. The state has thus understood the attractions and advantages of these two cultural models and included elements of the two alternatives in the emerging Tajiki consciousness. The constructed identity as a whole serves the interests of the ruling élite well—embracing an Iranian heritage while marginalising Iran, making overtures towards Islam while discounting and excluding Islamists, positioning the country as the birthplace of the European nations while sidelining Uzbekistan, and maintaining a common cultural currency with Russia. Nevertheless, Tajiki identity is still quite fragile and faces a number of challenges: an increasingly diglossic language situation, as well as large communities of speakers of minority languages (especially Russian and Uzbek); the lack of popular identification with the constructive national consciousness; the popular turn towards Islam; and the exclusion of the significant Uzbek minority (and poor relations with neighbouring Uzbekistan). Ultimately, long-term success for Tajik identity will necessitate embracing its shared Central Asian heritage and the adoption of an inclusivist, non-essentialist approach towards its culture and past.

This article is a summary of a paper, ‘Iranian and Islamic heritage and the formation of Tajiki national identity’, presented at the conference, ‘After the Persianate: Cultural heritage and national transformation in modern Iran and India’, organised by the Iranian Studies Program, College of International Studies, University of Oklahoma, 07–08 March 2014, Norman, Oklahoma. I thank Sitora Usmonova Lewental for her assistance in carrying out fieldwork and for her input on this paper.

References and citations

- The Russian Orientalist Vasiliĭ Vladimirovich Bartolʹd (1869–1930) observed that a Persian court official used the phrase ‘we Tajiks (mā tāzīkān)’ in the Tārīkh-e Masʿūdī by the Ghaznavid historian Abū ol-Fażl Bayhaqī (955–1077); Encyclopædia of Islam, 2nd ed., s.v., ‘Tād̲j̲īk’. [↑]

- Schoeberlein-Engel, ‘Identity in Central Asia’, 118; Bergne, Birth of Tajikistan, 7. [↑]

- See Laruelle, ‘Return of the Aryan myth’, 54. [↑]

- Ibid., 58. [↑]

Bibliography and further reading

Bashiri, Iraj, ed. The Samanids and the revival of the civilization of Iranian peoples. Dushanbe: Irfon, 1998. [online]

Beeman, William O. ‘The Struggle for identity in post-Soviet Tajikistan’. Middle East Review of International Affairs 3.4 (December 1999). [online]

Bergne, Paul. The Birth of Tajikistan: National identity and the origins of the republic. London/New York City: I B Tauris, 2007.

Blakkisrud, Helge and Shahnoza Nozimova. ‘History writing and nation building in post-independence Tajikistan’. Nationalities Papers 38.2 (March 2010): 173–189 (DOI 10.1080/00905990903517835).

Laruelle, Marlène. ‘The Return of the Aryan myth: Tajikistan in search of a secularized national ideology’. Nationalities Papers 35.1 (March 2007): 51–70 (DOI 10.1080/00905990601124462).

Naumkin, Vitalii Viacheslavovich. Radical Islam in Central Asia: Between pen and rifle. The Soviet bloc and after. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005.

Payne, John. ‘Tajikistan and the Tajiks’. In The Nationalities question in the post-Soviet states, ed. Graham Smith, 367–384. London/New York City: Longman, 1996.

Schoeberlein-Engel, John Samuel. ‘Identity in Central Asia: Construction and contention in the conceptions of “Özbek”, “Tâjik”, “Muslim”, “Samarqandi” and other groups’. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, 1994.

Suny, Ronald Grigor. ‘Provisional stabilities: The Politics of identities in post-Soviet Eurasia’. International Security 24.3 (Winter 1999–2000): 139–178. [JStor] [online (.doc)]

Sypko, Susan. ‘Tajiks wrestle with identity and Islam’. Far Eastern Economic Review 170.8 (October 2007): 41–45.

Image credits

- Tajiki one-hundred somoni note depicting the Sāmānid ruler Esmāʿīl, emphasising the connexion between modern Tajikistan and the Ninth/Tenth-Century state. Source: Wikipedia.

- Map of mediæval trade routes in Central Asia. Source: William R Shepherd, Historical atlas (New York City: Henry Holt and Company, 1923), 102-103.

- Presidents Maḥmūd Aḥmadī-nezhād, Emōm-ʿAlī Raḥmōn, and Ḥāmid Karzay of Iran, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan meeting in Kuwait, 2012. Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Tajikistan.

- Tajiks praying in the central mosque of Dushanbe, 2010. Source: Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Presidents Vladimir Putin and Emōm-ʿAlī Raḥmōn of Russia and Tajikistan, in a meeting in Moscow, 2013. Source: Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Reuters).

- Tajik celebration. Source: Inspiration Import (web log).