A Brief analysis of ‘Saddām’s Qādisiyyah’

This article is a summary of a paper, ‘“Saddam’s Qadisiyyah”: Religion and history in the service of state ideology in Baʿthi Iraq’ published in Middle Eastern Studies 50.6 (November 2014), 891–910 (DOI 10.1080/00263206.2013.870899). Part of the paper was presented as ‘History for a purpose: An Analysis of “Ṣaddām’s Qādisiyyah”’, at the 5th annual conference of the Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa, 12 October 2012, Washington, DC. [online]

Table of contents

1. Redefining al-Qādisiyyah

Demonstrating the success of Ṣaddām’s rhetoric is the response it received from both Arab governments and Western observers alike; they accepted his interpretation of al-Qādisiyyah without hesitation, even using his analogy to explain contemporary enmity between Iran on the one hand and the Arab world as a whole. Saʿūdī, Jordanian, and Egyptian officials all echoed Iraq’s claims that the ‘racist Persian régime’ sought to avenge its defeat at al-Qādisiyyah. Western journalists described the war as an age-old ethnic clash dating back at least as far as al-Qādisiyyah, if not thousands of years.

2. ‘Arab-Islamist’ rhetoric

Indeed, references by other radical Islamist groups to al-Qādisiyyah in their rhetoric and symbols—including militant brigades, training camps, mosques, Islamic law courts, and the content of sermons—represent a new chapter in the modern narrative of al-Qādisiyyah.2 Like Ṣaddām, these parties recognise the value of religious history and seek to harness its emotive power in their contemporary political struggles. Thus, the initial battleground for these campaigns is that of collective memory; indeed, the theme of (Arabs) remembering and (Iranians) forgetting the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah appeared frequently in Ṣaddām’s speeches. Nevertheless, one might take comfort in the hope that an inclusive and non-essentialist approach to the engagement, which disperses with useless and injurious dichotomies, might yet emerge.

References and citations

- For a detailed study on the historiography of al-Qādisiyyah and its changing perceptions through time, see Lewental, ‘Qādisiyyah, then and now’. For a short examination of al-Qādisiyyah nomenclature in the modern Middle East, including an exhaustive list of examples, see idem, ‘Qādisiyyah in modern Middle Eastern discourse’. [↑]

- For a short examination of al-Qādisiyyah in radical Islamist rhetoric, see Lewental, ‘Early Islamic history and memory in radical Islamist discourse’. [↑]

Bibliography and further reading

Baram, Amatzia. Culture, history, and ideology in the formation of Baʿthist Iraq, 1968–69. New York City: St Martin’s Press, 1991.

Bengio, Ofra. Saddam’s word: Political discourse in Iraq. New York City: Oxford University Press, 1998 (DOI 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195114393.001.0001).

Davis, Eric M. Memories of state: Politics, history, and collective identity in modern Iraq. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Dawisha, Adeed I. ‘Arabism and Islam in Iraq’s war with Iran’. Middle East Insight 3 (1984): 32–33.

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Early Islamic history and memory in radical Islamist discourse’. Online article. DGLnotes.com, 12 June 2013. [online]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Qādisiyyah in modern Middle Eastern discourse’. Online article. DGLnotes.com, 21 November 2005. [online]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Qādisiyyah, then and now: A Case study of history and memory, religion, and nationalism in Middle Eastern discourse’. PhD dissertation, Department of Near Eastern & Judaic Studies, Brandeis University, 2011. [abstract]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘“Saddam’s Qadisiyyah”: Religion and history in the service of state ideology in Baʿthi Iraq’. Middle Eastern Studies 50.6 (November 2014), 891–910 (DOI 10.1080/00263206.2013.870899). [online]

Makiya, Kanan. The Monument: Art, vulgarity, and responsibility in Iraq. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1991.

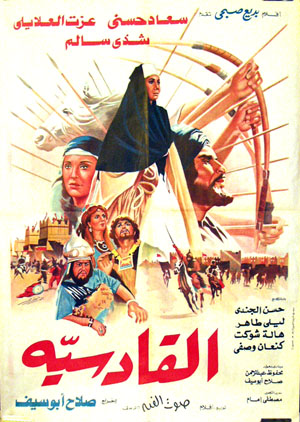

Rida, Muhammad. ‘Qadisiyya: A New stage in Arab cinema’. Ur 3 (1981): 40–43.

Ṣaddām Ḥusayn. ‘President visits scene of grenade incident 2 Apr’. Baghdād, Voice of the Masses in Arabic. 02 April 1980, 1200 GMT. FBIS-MEA-80-066. 03 April 1980, E2–3.

Related links

Image credits

- A Baghdād mural depicting Ṣaddām Ḥusayn surveying both the Seventh-Century and the ‘modern’ Battles of al-Qādisiyyah. Source: unknown; similar image appears in Baram, plate 15.

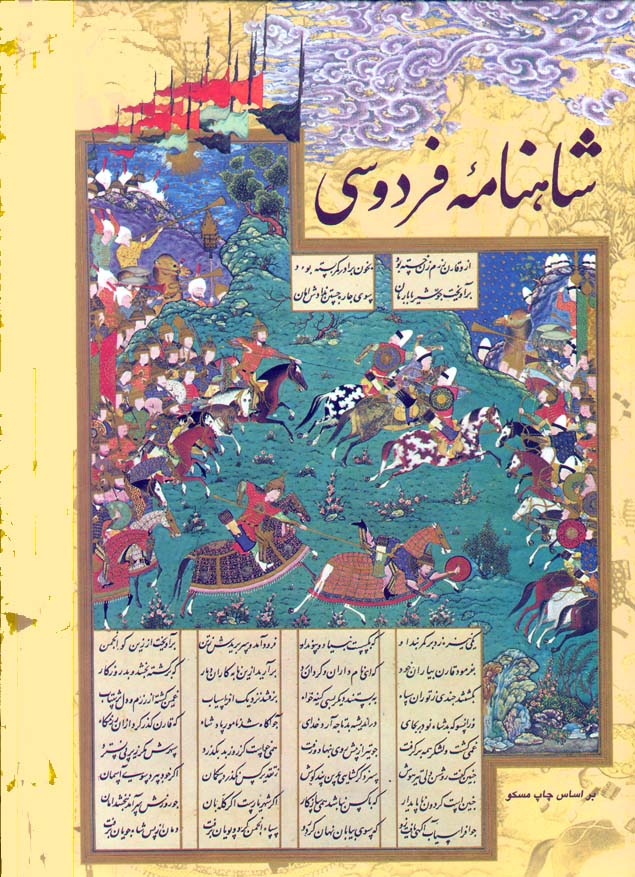

- Depiction of the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah from a manuscript of the Persian epic Shāh-nāmeh. Source: Wikipedia.

- Poster for the Egyptian film al-Qādisiyyah (1981). Source: MusicMan.com.

- Close-up of the fists in the Qaws an-Naṣr (‘Victory Arch’), sometimes called the ‘Swords of Qādisiyyah’, modelled after Ṣaddām’s own. Source: jamesdale10 (Everystockphoto.com).

- Internet banner for a Sunnī militant group opposed to the Islamic Republic of Iran. Source: Qadesiyoon Media Brigade (website 1) Qadesiyoon Media Brigade (website 2).