Ben-Yehūdāh’s ‘Sources to fill the lacunæ in our language’

Table of contents

Introduction

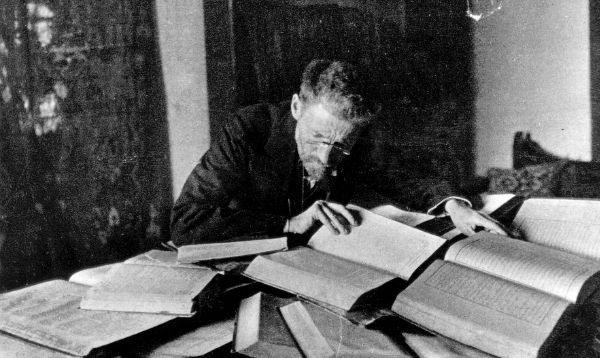

The need to create new words to fill the lacunæ in our language is sensed increasingly frequently in time of late. The day when our language will become that of instruction in institutions of higher education is approaching and then we will be hard-pressed to fill in its gaps. For this reason, the Waʿad ha-Lāshōn (Language Committee) has devoted part of the time in its meetings to this question about which Mr Elīʿezer Ben-Yehūdāh presented the following words, which provided material for the discussions and the conclusions.

I. First session

1. The Lacunæ in our language

According to the founding principles of the Committee, our work falls into two categories. The first is the gathering of all words not known to the public-at-large from our ancient and modern literature and to use these words in everyday life. This endeavour is not cerebral, but rather an effort that is merely laborious. Certainly, should we choose to focus our energies on studying the meaning of words and determining scientifically their connotation, then this process would necessitate scholarly knowledge. However, it has already become clear that the Committee, save for the occasional exception, cannot spend the precious time it has for its practical efforts on such scientific research that would demand wide-ranging and deep research. Furthermore, it is difficult to reach definitive conclusions regarding scientific investigations when they are settled subjectively by majority opinion. For this reason, the Committee has decided to avoid, as much as it is possible, the use of words for which their meaning is unclear and about which there is disagreement between the interpreters and scholars. In addition, there is always the possibility of a dissenter who will disagree and side with the interpretation of one scholar and not with the Committee’s consensus. As such, the Committee should avoid this right now, since it has decided to engage in discussions with linguists abroad and it is well known that those scholars adhere firmly to scientific principles and do not yield even an inch—any one of them would maintain their opinion with utmost conviction regarding a word whose meaning is uncertain.

For this reason, against our will, we must resign ourselves to the collection of only those words for which there is no doubt about their meaning and this, as I have stated, is no intellectual effort, but rather, simple labour.

One must note further that this aspect of our endeavour, aside from lacking any serious academic qualities, also contributes very little to the Committee’s goal. We must engage in this effort, lest we err in the creation of a new word when an old term for the desired concept already exists; however, there is not doubt that this work will not bring us great gains, for, while there are countless words in our literature that are unknown to the public, most of them relate to abstract matters and some to the sciences, but for the needs of everyday life which we require, there is a very small number of words which we have left to find in the ancient literature or even in the literature dating after the time of the Talmud and the Midrash.

But these are the lacunæ that we can only fill through the second aspect of our work, which is the creation of new words—an effort that is truly more cerebral than laborious.

2. On linguistic innovation

In times past, the notion that linguistic innovation was forbidden reigned supreme not only among us, but among the nations of the world, and many chronicles record scholars’ reliance upon this dogma. For example,2 there is the case of the emperor Tiberius,3 who once produced a word that was not in accordance with Latin grammar, and in his presence were two of the Roman grammarians, Marcellus and Capito,4 and the former criticised the emperor for having made a grammatical mistake. However, Capito, who was apparently more of a courtier than a grammarian, exclaimed: ‘Latin grammar is determined by how the emperor speaks, and if that is not the case today, then it will be so tomorrow’. Marcellus replied, ‘Capito is a liar! The Roman emperor can grant Roman citizenship to any man who should desire Roman sovereignty, but not to words or linguistic forms. And a similar case took place with the emperor Sigismund5 at the ecumenical Council of Constance,6 when he exhorted the monks to root out the Hussite heresy,7 saying in Latin:

Videte Patres ut eradicetis schismam hussitarum!8

To which one of the monks called out:

Serenissime Rex, schisma est generis neutri.9

The emperor asked the monk, ‘How do you know this?’ The monk replied, ‘Alexander Gallus10 says so’. ‘And who is Alexander Gallus?’ asked Sigismund. The monk answered, ‘He was a monk!’. ‘And I’, replied Sigismund, ‘am an emperor of Rome, and what I say matters more than what a monk says’. The scholar Max Müller,11 who cited this example in his book The Science of language, concludes, ‘No doubt the laughers were with the emperor; but for all that, schisma remained a neuter, and not even an emperor could change its gender or termination’.12

References and citations

- See Lewental, ‘Rasmī or aslī?’. [↑]

- Ben-Yehūdāh took this, and the following anecdote, from Max Müller’s Lectures on the science of language. See Müller, Lectures on the science of language, 5th ed., vol. 1 (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1866), 40-41. [↑]

- Tiberius, the second Roman emperor, ruled from 14 to 37 CE. [↑]

- In his work De grammaticis et rhetoribus, the Roman historian Suetonius (Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, c. 69/75–after 122) described Marcus Pomponius Marcellus as ‘a most pedantic critic of the Latin language’; idem, Suetonius, transl. John Carew Rolfe, vol. 2 (London & New York City: William Heinemann; Macmillan), §XXII, 426-429. Gaius Ateius Capito (c. 30 BCE–22 CE) was a Roman jurist, senator, and, briefly, a consul during the early First Century. [↑]

- Sigismund of Luxemburg (1368–1437) served as king of Hungary and Croatia, Germany, and Bohemia, before becoming Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1433–1437). [↑]

- The Council of Constance (1414–1418) was the fifteenth ecumenical council; while ending the Three-Popes Controversy, it condemned and executed the Czech reformer Jan Hus (c. 1369–1415), which eventually led to the Hussite or Bohemian Wars (1419–1434). [↑]

- The Hussite ‘heresy’, inspired by the Czech reformer Jan Hus (c. 1369–1415), was a Christian reform movement that preceded the Protestant Reformation and culminated in an armed rebellion by its largely Czech adherents against Catholic control. [↑]

- Translation: ‘See (to it), fathers, that you eradicate the Hussite schism!’ [↑]

- Translation: ‘Most serene king, (the word) schisma [schism] is of the neuter gender’. [↑]

- Alexander of Villedieu (or Alexander Gallus, c. 1175–1240) was a Breton poet and grammarian, mathematician, teacher at the University of Paris, and Franciscan monk. [↑]

- Friedrich Max Müller (1823–1900) was a German philologist, who pioneered the fields of Indology and comparative religious studies. [↑]

- Müller, Lectures, I 41. [↑]

- a. [↑]

Bibliography and further reading

Ben-Yehūdāh, Elīʿezer. ‘Meqōrōt: Le-malléʾ he-ḥāsér bi-leshōnénū [Sources to fill the lacunæ in our language]’. Zikhrōnōt Waʿad ha-Lāshōn 4 (1914/5674): 3–14. [online] [online (text)]

Ben-Yehūdāh, Elīʿezer. ‘Sheʾelāh lōheṭāh (nikhbedāh) [A burning (weighty) question]’. In ha-ʿIvrīt bat-zmannénū: Meḥqārīm we-ʿiyyūnīm [Studies on contemporary Hebrew], ed. Shelomo Morag, 3–15. Vol. 1. Jerusalem: Academon Press, 1987. [online (text)]

Müller, Max. Lectures on the science of language. 5th ed. 2 vols. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1866. [online]

Yahudah, Abraham Shalom. ‘Tōʿelet leshōnōt ʿArāv la-havānat ha-miqrāʾ [The Utility of the Arab languages in understanding the Bible]’. Zikhrōnōt Waʿad ha-Lāshōn 6 (1928): 19–23. [online]

Transliteration tables

For Arabic, I have chosen to conform to the basics of the system used in the International Journal of Middle East Studies, the new Encyclopædia of Islam (3rd ed.), and the Library of Congress, with two major exceptions: I always mark the tāʾ marbūṭah (ة) with an ‘h’ and I assimilate the definite article (al-) into the sun letters, both stemming from an effort to make the transliterations approximate both orthography and pronunciation.

For Hebrew transliteration, I have adopted a similar method that makes it easier to compare the two languages.

Related links

Image credits

- Ben-Yehūdāh working at his desk in Jerusalem, c. 1912. Source: Shlomo Narinsky (David B Keidan Collection of Digital Images, Central Zionist Archives).

- Artistic rendering of the Hebrew and Arabic words for ‘peace’, shālōm and salām, respectively, in a style demonstrating their graphic resemblance, against the backdrop of the Old City of Yāfō (Jaffa). Source: D Gershon Lewental (DGLnotes).

- Members of PaLMaḤ‘s ‘Arab department’, known as mistaʿaravīm, from Qibbuts Yagur, near Ḥaifa. Source: Qibbūts Yāgūr.

- Yemenite immigrants being brought to Israel during the rescue mission of Operation ‘Magic Carpet’, 1949–1950. Source: Wikipedia.