Primary sources on the Bajīlah’s ‘fourth’

Overview

Table of contents

5. aṭ-Ṭabarī (d. 923)

5.1 Abū Jaʿfar [aṭ-Ṭabarī]←as-Sarī b. Yaḥyā←Shuʿayb b. Ibrāhīm←Sayf b. ʿUmar←Muḥammad b. Nuwayrah, Ṭalḥah [b. Aʿlam al-Ḥanafī], Ziyād [b. Sarjis al-Aḥmarī], and ʿAṭiyyah [b. al-Ḥārith al-Hamdānī]

… [ʿUmar ordered Jarīr to head to Iraq, but Jarīr insisted on Syria.] When [the Bajīlah] had gone forth to (join) Jarīr and he had ordered them to meet at the appointed time, ʿUmar gave him compensation for having compelled him and to benefit him, making over to him a quarter of the fifth of what God had bestowed on them as spoils in their campaigns. This was for him, those who gathered to him, and those who had been brought forth to him from among the tribes. …

Source: aṭ-Ṭabarī, Annales, I 2183 (Arabic); English translation from idem, Challenge to the empires, 196.

5.2 as-Sarī [b. Yaḥyā]←Shuʿayb [b. Ibrāhīm]←Sayf [b. ʿUmar]←ʿAṭiyyah [b. al-Ḥārith al-Hamdānī] and Sufyān al-Aḥmarī←al-Mujālid [b. Saʿīd]←ash-Shaʿbī

When the army of the Bajīlah was collected, ʿUmar said, Come to us on your own way

. … [The Bajīlah preferred to go to Syria, but ʿUmar wished them to head to Iraq.] He did not cease insisting to them and they refusing him until that was decided on and he assigned them a quarter of the fifth of what God had bestowed on the Muslims as booty, in addition to their [proper] share of the booty. He appointed ʿArfajah to be in charge of those Bajīlah who had been residing among the Jadīlah, and Jarīr [b. ʿAbd-Allāh] to be in charge of those who were living among the Banū ʿĀmir and others. … Then ʿUmar gave him charge of the main part of the Bajīlah. … [Jarīr undermined ʿArfajah amongst the Bajīlah and had them complain about him.] [ʿUmar] then appointed Jarīr in his place, bringing together the Bajīlah under him. He also revealed to Jarīr and the Bajīlah that he would send ʿArfajah to Syria; that made Jarīr like Iraq. …

Source: aṭ-Ṭabarī, Annales, I 2186 (Arabic); English translation from idem, Challenge to the empires, 199.

5.3 as-Sarī [b. Yaḥyā]←Shuʿayb [b. Ibrāhīm]←Sayf [b. ʿUmar]←Ismāʿīl b. Abī Khālid←Qays b. Abī Ḥāzim

The Persians sent in the direction of the tribe of Bajīlah thirteen elephants.

Source: aṭ-Ṭabarī, Annales, I 2298 (Arabic); English translation from idem, Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, 92.

5.4 as-Sarī [b. Yaḥyā]←Shuʿayb [b. Ibrāhīm]←Sayf [b. ʿUmar]←Ismāʿīl b. Abī Khālid

The Battle of al-Qādisiyyah took place at the beginning of Muḥarram of the year 14. A [Muslim] man went out to the Persians. They said to him: Direct us!

He directed them towards the Bajīlah, and they sent in the direction of Bajīlah sixteen elephants.

Source: aṭ-Ṭabarī, Annales, I 2298 (Arabic); English translation from idem, Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, 92.

5.5 Ibn Ḥumayd←Salamah [b. al-Faḍl]←Muḥammad b. Isḥāq←Ismāʿīl b. Abī Khālid, a client of the Bajīlah←Qays b. Abī Ḥāzim al-Bajalī, who participated in the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah on the side of the Muslims

A man from the tribe of Thaqīf was with us on the day of al-Qādisiyyah. He joined the Persians as a renegade and informed them that the Muslims in the area held by Bajīlah had (the most) courage and valour. We were [only] one-quarter of the Muslims, but they sent against us sixteen elephants and sent only two elephants against the rest. They scattered iron spikes under the feet of our horses and sprayed us with arrows, so that it was as if rain were falling upon us. They tied their horses to each other so that they could not run away.

ʿAmr b. Maʿdīkarib used to pass by and say: O Emigrants, be lions! A lion is a man who takes care of his affairs on his own. When a Persian drops his spear, he is nothing but a stupid goat

. There was a Persian commander whose arrow never missed the target. We said to ʿAmr b. Maʿdīkarib: O Abū Thawr, beware of this Persian, because his arrow never misses the target

. ʿAmr turned toward him. The Persian shot at him an arrow which hit his bow. ʿAmr fell upon him, seized him by the neck, and slew him, taking from him two golden bracelets, a gold-plated belt, and a brocade coat.

[The khabar continues with an account of the killing of Rostam, the defeat of the Persians, and some skirmishes that followed the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah. It then includes two sets of verses criticising Saʿd.]

Source: aṭ-Ṭabarī, Annales, I 2355-2356 (Arabic); English translation from idem, Battle of al-Qādisiyyah, 140. (Cf. Abū Yūsuf, 1.1.)

6. al-Jaṣṣāṣ (917–981)

A famous Ḥanafī jurist, Aḥmad b. ʿAlī Abū Bakr ar-Rāzī (917–Nīshāpūr, 14 August 981) studied first in Baghdād under ʿAlī b. Ḥasan al-Karkhī, before travelling to study in Nīshāpūr, in north-eastern Iran. After al-Karkhī died, he returned to Baghdād and, later, became the head of the Ḥanafī school in Baghdād. Twice, he received nominations for the office of judge, but declined the position. (Biography based upon Spies, II 486.)

6.1 Ismāʿīl b. Abī Khālid←Qays b. Abī Ḥāzim

[Forthcoming.]

7. al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī (1002–1071)

7.1 Abū ʿAlī Ismāʿīl b. Muḥammad b. Ismāʿīl aṣ-Ṣaffār←Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥasan b. ʿAlī b. ʿAffān al-Kūfī←Yaḥyā b. Ādam←Ibn Abī Zāʾidah←Ismāʿīl b. Abī Khālid←Qays b. Abī Ḥāzim

[Forthcoming.]

7.2 al-Ḥasan b. Abī Bakr [al-Bazzāz]←ʿAbd-Allāh b. Isḥāq b. Ibrāhīm al-Baghawī←ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz [al-Baghawī]←Abū ʿUbayd al-Qāsim b. Salām [al-Harawī]←Hushaym [b. Bashīr as-Salamī]←Ismāʿīl [b. Abī Khālid]←Qays [b. Abī Ḥāzim]

[Forthcoming.]

Bibliography and further reading

Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb b. Ibrāhīm al-Kūfī. Kitāb al-kharāj. 1st edition. Cairo: al-Maṭbaʿah as-Salafiyyah wa-maktabatuhā, 1934.

Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb b. Ibrāhīm al-Kūfī. Taxation in Islām. Ed. and transl. from Arabic by Aharon Ben Shemesh. Vol. 3, Abū Yūsuf’s Kitāb al-kharāj. Leiden & London: E J Brill; Luzac, 1969.

al-Balādhurī, Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā. Liber expugnationis regionum. 2nd ed. Ed. Michael Jan de Goeje. 1866. Reprint, Leiden: E J Brill, 1968. [online]

al-Balādhurī, Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā. The Origins of the Islamic state, being a translation from the Arabic accompanied with annotations, geographic and historic notes of the Kitâb futûḥ al-buldân of al-Imâm abu-l ʿAbbâs Aḥmad ibn-Jâbir al-Balâdhuri. Khayats Oriental reprint, 11. Ed. and transl. from Arabic by Philip Khuri Hitti. Vol. 1. 1916. Reprint, Beirut: Khayats, 1966. [online]

Becker, Carl Heinrich. ‘al-Balād̲h̲urī, Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā b. Ḏj̲ābir b. Dāwūd’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 1, 971 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0094).

Bosworth, Clifford Edmund. ‘al-Ṭabarī, Abū Ḏj̲afar Muḥammad b. Ḏj̲arīr b. Yazīd’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 10, 11–15 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1133).

Donner, Fred McGraw. The Early Islamic conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. [online (excerpt)]

Görke, Andreas. ‘Eschatology, history and the common link: A Study in methodology’. In Method and theory in the study of Islamic origins, ed. Herbert Berg, 179–208. Islamic history and civilization: Studies and texts, 49. Leiden/Boston: E J Brill, 2003 (DOI 10.1163/9789047401575_012).

Ibn Abī Shaybah, Abū Bakr ʿAbd-Allāh b. Muḥammad al-Kūfī. Kitāb al-Muṣannaf fī al-aḥādīth wa-ʾl-athār. 15 vols. 1st ed. Riyāḍ: Maktabat ar-Rushd Nāshirūn, 2004/1425.

al-Jaṣṣāṣ, Aḥmad b. ʿAlī Abū Bakr al-Rāzī. Aḥkām al-Qurʾān. 5 vols. Ed. Muḥammad al-Ṣādiq Qamḥawī. Beirut: Dār Iḥyāʾ al-Turāth al-ʿArabiyyah, 1992/1312. [online]

Juynboll, Gautier H A. ‘(Re)appraisal of some technical terms in ḥadīth science’. Islamic Law & Society 8.3 (2001): 303–349 (DOI 10.1163/156851901317230611). [JStor]

Juynboll, Gautier H A. ‘Some isnād-analytical methods illustrated on the basis of several woman-demeaning sayings from ḥadīth literature’. In Ḥadīth: Origins and developments, ed. Harald Motzki, 175–216. The Formation of the classical Islamic world, 28. Aldershot, UK/Burlington: Ashgate/Variorum, 2004.

al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī, Abū Bakr Aḥmad b. ʿAlī ash-Shāfiʿī. Taʾrīkh Baghdād. 17 vols. 1st ed. Beirut: Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, 2001/1422.

Landau-Tasseron, Ella. ‘Sayf ibn ʿUmar in medieval and modern scholarship’. Der Islam 67.1 (1990): 1–26 (DOI 10.1515/islm.1990.67.1.1).

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Qādisiyyah, then and now: A Case study of history and memory, religion, and nationalism in Middle Eastern discourse’. PhD dissertation, Department of Near Eastern & Judaic Studies, Brandeis University, 2011. [abstract]

Morony, Michael G. Iraq after the Muslim conquest. 1st ed. 1984. Reprint, Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press, 2005.

Motzki, Harald. ‘Dating Muslim traditions: A Survey’. Arabica 52.2 (April 2005): 204–253 (10.1163/1570058053640349). [JStor]

Noth, Albrecht, in collaboration with Lawrence Irving Conrad. The Early Arabic historical tradition: A Source-critical study. Studies in late antiquity and early Islam, 3. Translated from German by Michael Bonner. 2nd edition. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1994.

Pellat, Charles. ‘Ibn Abī S̲h̲ayba, Abū Bakr ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm (= Abū S̲h̲ayba) b. ʿUt̲h̲mān al-ʿAbsī al-Kūfī’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 3, 692 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3055).

Schacht, Joseph. ‘Abū Yūsuf Yaʿḳūb b. Ibrāhīm al-Anṣārī al-Kūfī’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 1, 164–165 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_0277).

Schmucker, Werner. ‘Yaḥyā b. Ādam b. Sulaymān’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 11, 243–245 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7948).

Sellheim, Rudolf. ‘al-Ḵh̲aṭīb al-Bag̲h̲dādī, Abū Bakr Aḥmad b. ʿAlī b. T̲h̲ābit b. Aḥmad b. Mahdī al-S̲h̲āfiʿī, known as al-Ḵh̲aṭīb al-Bag̲h̲dādī’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 4, 1111–1112 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_4235).

Spies, Otto. ‘al-Ḏj̲aṣṣāṣ, Aḥmad b. ʿAlī Abū Bakr al-Rāzī’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 2, 486 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_2017).

al-Ṭabarī, Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr. Annales quos scripsit Abu Djafar Mohammed ibn Djarir at-Tabari. 15 vols. Ed. Michael Jan de Goeje, Jakob Barth, Theodor Nöldeke, et al. Leiden: E J Brill, 1879–1901. [online (vol. 4)] [online (vol. 5)]

al-Ṭabarī, Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr. The History of al-Ṭabarī. Bibliotheca Persica. Transl. from Arabic by Khalid Yahya Blankinship. Vol. 11, The Challenge to the empires: A.D. 633–635/A.H. 12–13. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993.

al-Ṭabarī, Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr. The History of al-Ṭabarī. Bibliotheca Persica. Translated from Arabic by Yohanan Friedmann. Vol. 12, The Battle of al-Qādisiyyah and the conquest of Syria and Palestine: A.D. 635–637/A.H. 14–15. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Yaḥyā b. Ādam al-Qurashī. Le livre de l’impôt foncier. Ed. Theodoor Willem Jan Juynboll. Leiden: E J Brill, 1896. [online]

Yaḥyā b. Ādam al-Qurashī. Taxation in Islām. Ed. and transl. from Arabic by Aharon Ben Shemesh. Vol. 1, Yaḥyā ben Ādam’s Kitāb al-kharāj. 2nd revised edition. Leiden: E J Brill, 1967.

Related links

Image credits

- al-Baṭḥā, a contemporary settlement in the Sawād, on the banks of the Euphrates River. Source: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology: Mesopotamian landscapes.

- Satellite image of the Middle East, with super-imposed political borders. The Sawād is visible as the dark expanse of land in south-central Iraq. Source: NASA.

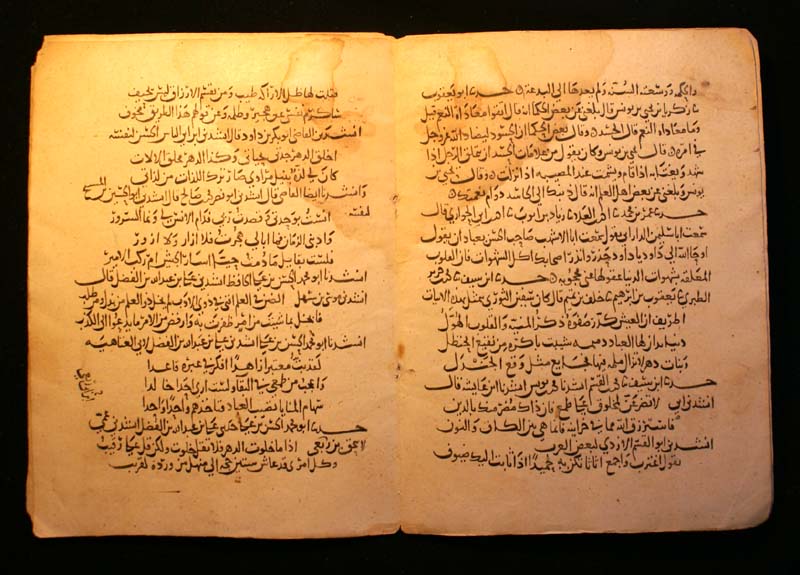

- A manuscript page, dating to the early Thirteenth Century, from a Persian translation of aṭ-Ṭabarī’s Qurʾān commentary. Source: Wikipedia.

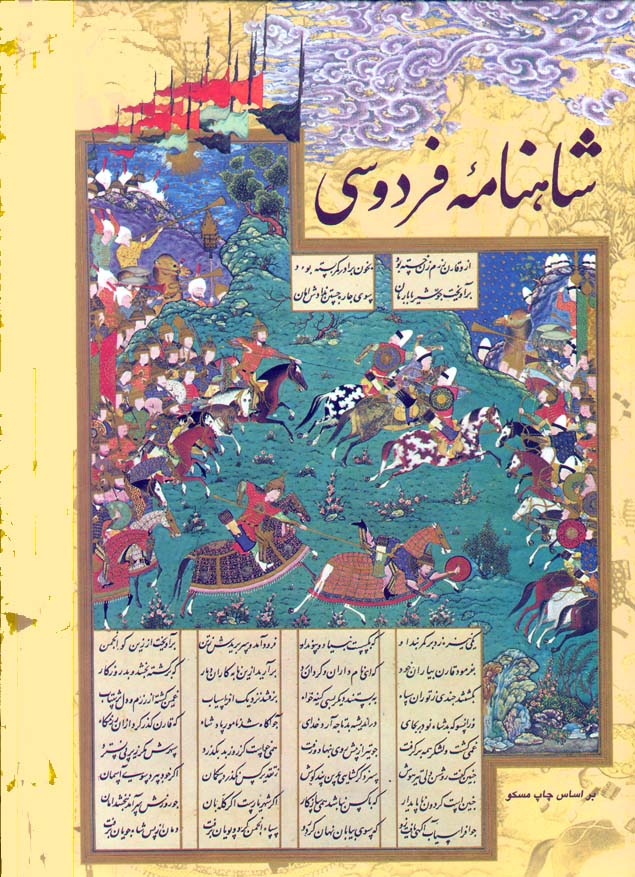

- Depiction of the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah from a manuscript of the Persian epic Shāh-nāmeh. Source: IranProud internet forum.

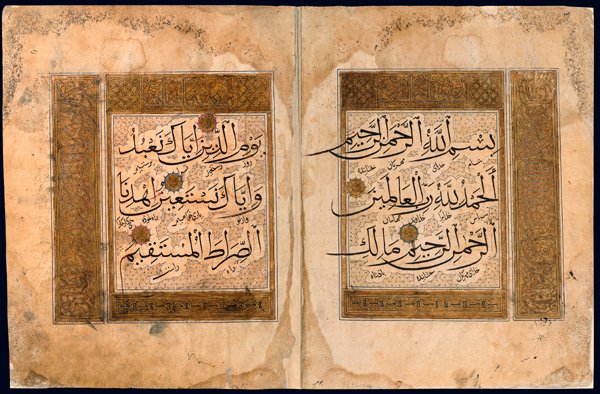

- An Arabic manuscript dating to the late ʿAbbāsid period. Source: Wikipedia .