Qādisiyyah in modern Middle Eastern discourse

Overview

Table of contents

2. Modern manipulation of al-Qādisiyyah

2.1 Qādisiyyat-Ṣaddām: The Iran-Iraq War

Ṣaddām’s Qādisiyyah (Ar. Qādisiyyat-Ṣaddām). The first instance of this naming occurred on 02 April 1980, a half-year before the outbreak of hostilities, on the occasion of a visit by Ṣaddām Ḥusayn to al-Mustanṣiriyyah University in Baghdād, where a bomb attack on the previous day had injured his vice-president, Tarīq ʿAzīz. Ṣaddām blamed the newly-founded Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and, drawing the parallel to the Seventh-Century battle, he announced:

In your name, brothers, and on behalf of the Iraqis and Arabs everywhere we tell those [Persian] cowards and dwarfs who try to avenge Al-Qadisiyah that the spirit of Al-Qadisiyah as well as the blood and honor of the people of Al-Qadisiyah who carried the message on their spearheads are greater than their attempts (see Ṣaddām, E3).

The maquette was worked from plaster casts of the [Ṣaddām]’s arms, taken from just above the elbow, with a sword inserted into each fist. The monument serves as a Baʾthi equivalent of the Arc de Triomphe in the Champs Elysées. The Baʾthi arch, however, is bigger. The President’s forearms and fists, sixteen metres in length (the same height as the Arc de Triomphe), burst out of the ground like gargantuan bronze tree-trunks and rise with their firmly grasped swords to an apex forty metres above the ground. War debris in the shape of five thousand Iranian helmets taken fresh from the battelfield [sic] are gathered up in two nets (2,500 each) which are torn asunder at the base, scattering the helmets around the points at which the arms rise from the earth. … [T]he raw steel used [for the swords] was obtained by melting down the weapons of Iraqi ‘martyrs’ who died in the fighting (see Makiya, 3-4).

2.2 Radical Islamists and al-Qādisiyyah

God is most great (Ar. Allāhu akbar) to the country’s flag and arranged for a fringe group to declare him the caliph of Islam. This trend towards religio-political manipulation of al-Qādisiyyah has continued most prominently among the proponents of radical Islam, who have cited the battle as an inspirational example of a small, but righteous and zealous group overcoming a wicked and immoral reigning super-power. Thus, for example, a group of insurgents operating against the American-led coalition forces in Iraq called itself Luwāʾ Qādisiyyat Saʿd (Saʿd’s Qādisiyyah Brigade). In particular, Sunnī radicals, such as those active in al-Qāʿidah (al-Qaeda), have cited al-Qādisiyyah in their messages to the faithful. In January 2011, the Global Islamic Media front, a European propaganda organisation that supports al-Qāʿidah and other radical groups, announced the creation of al-Qadisiyyah Media Productions, which would translate Arabic-language materials into South Asian languages, including Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Pashto, and Persian. Likewise, a branch of a Sunnī militant group opposed to the Islamic Republic of Iran calls itself the Qadesiyoon Media Brigade on the Internet, seeking apparently to follow in the footsteps of the Seventh-Century invaders and to overturn to the government of Iran.

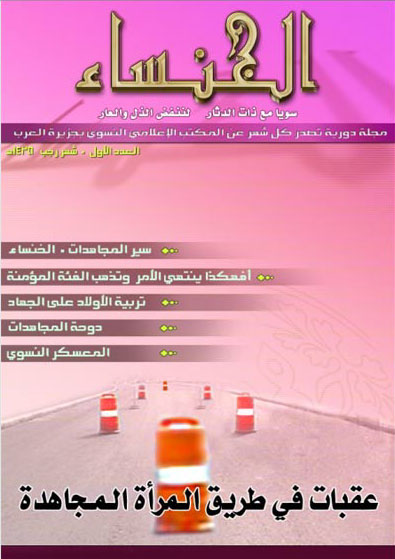

2.2.1 The Example of al-Khansāʾ

Oh the mother of men, how many sons do you have? … Are you not taking the female predecessors as an example and role model? Give what they gave, so you may attain a reward like theirs. [Al-Khansāʾ] is a famous woman, who, if our women were like her, no one would remain behind. If the women were like her, the men would leave for jihad in groups. … [When] news of [her sons’] deaths reached their mother, … she said: Praise be to God who honored me with their deaths, and I hope my God will gather me with them in His everlasting mercy

(see ʿAyyīrī).

Such invocations demonstrate the appeal of the Qādisiyyah narrative to radical Islamists, much as it attracted the attention of Ṣaddām Ḥusayn and the Baʿthist régime in Iraq. Although Ṣaddām and al-Qāʿidah may have highlighted different aspects or interpretations of Qādisiyyah, the memory of the Seventh-Century engagement continues to possess emotive significance in the modern Middle East.

Bibliography and further reading

Alavi, S M Ziauddin. Arab geography in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Aligarh: Department of Geography, Aligarh Muslim University, 1965.

al-ʿAyyīrī, Shaykh Yūsuf. ‘Shaykh Yusuf Al-Ayiri highlights women’s role in helping, hindering jihad’. Jihadist websites—OSC summary, 04 December 2009.

Baram, Amatzia. Culture, history, and ideology in the formation of Baʿthist Iraq, 1968–69. New York City: St Martin’s Press, 1991.

Bartolʹd, Vasiliĭ Vladimirovich [Wilhelm Barthold]. An Historical geography of Iran, ed. Clifford Edmund Bosworth. Modern classics in Near Eastern studies. Translated from Russian by Svat Soucek. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Bengio, Ofra. Saddam’s word: Political discourse in Iraq. New York City: Oxford University Press, 1998 (DOI 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195114393.001.0001).

Darwish, Mahmoud. ‘My beloved rises from her sleep’. Translated from Arabic by Ben M Bennani. Journal of Arabic Literature 6.1 (1975): 101–106 (DOI 10.1163/157006475X00078).

Davis, Eric M. Memories of state: Politics, history, and collective identity in modern Iraq. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Dawisha, Adeed I. ‘Arabism and Islam in Iraq’s war with Iran’. Middle East Insight 3 (1984): 32–33.

DeYoung, Terri. ‘Nasser and the death of elegy in modern Arabic poetry’. In Tradition and modernity in Arabic literature, ed. Issa J Boullata, Terri DeYoung, and Mounah Abdallah Khouri, 63–86. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Donner, Fred McGraw. The Early Islamic conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. [online (excerpt)]

Donner, Fred McGraw. Narratives of Islamic origins: The Beginnings of Islamic historical writing. Studies in late antiquity and early Islam, 14. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1998.

Gohar, Saddik. ‘The Protest poetry of Muhammad al-Fayturi and Langston Hughes’. Studies in Islam & the Middle East 4.1 (2007): 1–11. [online]

Gieling, Saskia Maria. Religion and war in revolutionary Iran. Library of modern Middle East studies, 18. London/New York City: I B Tauris, 1999.

Halbwachs, Maurice. The Collective memory. Translated from French by Francis J Ditter, Jr and Vida Yazdi Ditter. 1st ed. New York City: Harper & Row, 1980.

Halliday, Fred. Nation and religion in the Middle East. London: Saqi Books, 2000.

Haseeb, Khair el-Din, ed. Arab-Iranian relations. Beirut: Centre for Arab Unity Studies, 1998.

Humphreys, R Stephen. Between memory and desire: The Middle East in a troubled age. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1999.

Jandora, John Walter. The March from Medina: A Revisionist study of the Arab conquests. Clifton, New Jersey: Kingston Press, 1989.

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘A Brief analysis of “Ṣaddām’s Qādisiyyah”’. Online article. DGLnotes.com, 19 July 2012. [online]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Early Islamic history and memory in radical Islamist discourse’. Online article. DGLnotes.com, 12 June 2013. [online]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Qādisiyyah, then and now: A Case study of history and memory, religion, and nationalism in Middle Eastern discourse’. PhD dissertation, Department of Near Eastern & Judaic Studies, Brandeis University, 2011. [abstract]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘“Saddam’s Qadisiyyah”: Religion and history in the service of state ideology in Baʿthi Iraq’. Middle Eastern Studies 50.6 (November 2014), 891–910 (DOI 10.1080/00263206.2013.870899). [online]

Lewis, Bernard. History: Remembered, recovered, invented. New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

Lewis, Bernard. ‘Perceptions musulmanes de l’histoire et de l’historiographie’. In Itinéraires d’Orient: Hommages à Claude Cahen, ed. Raoul Curiel and Rika Gyselen, 77–81. Res Orientales, 6. Bures-sur-Yvette: Groupe pour l’étude de la civilisation du Moyen-Orient, 1994.

Long, Jerry Mark. Saddam’s war of words: Politics, religion, and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. 1st edition. Albany: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Makiya, Kanan. The Monument: Art, vulgarity, and responsibility in Iraq. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1991.

Morony, Michael G. Iraq after the Muslim conquest. 1st ed. 1984. Reprint, Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press, 2005.

Muir, Sir William. Annals of the early Caliphate, from original sources. London: Smith, Edler, & Co., 1883. [online]

Noth, Albrecht, in collaboration with Lawrence Irving Conrad. The Early Arabic historical tradition: A Source-critical study. Studies in late antiquity and early Islam, 3. Translated from German by Michael Bonner. 2nd edition. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1994.

Pourshariati, Parvaneh. Decline and fall of the Sasanian empire: The Sasanian-Parthian confederacy and the Arab conquest of Iran. International Library of Iranian Studies, 10. London/New York City: I B Tauris, 2008 (DOI 10.5040/9780755695270). [online]

Ram, Haggai. Myth and mobilization in revolutionary Iran: The Use of the Friday congregational sermon. Washington: American University Press, 1994.

Rida, Muhammad. ‘Qadisiyya: A New stage in Arab cinema’. Ur 3 (1981): 40–43.

Roy, Marina. ‘Saddam’s arms: Nationalist and Orientalist tendencies in Iraqi monuments’. Public 28 (Winter 2004): 56–76. [online]

Ṣaddām Ḥusayn. ‘President visits scene of grenade incident 2 Apr’. Baghdād, Voice of the Masses in Arabic. 02 April 1980, 1200 GMT. FBIS-MEA-80-066. 03 April 1980, E2–3.

Skarżyńska-Bocheńska, Krystyna. ‘Le reflet de l’Islam dans la poésie tunisienne contemporaine’. Die Welt des Islams 23.1–4 (1984): 182-197 (DOI 10.1163/157006084X00135).

Streck, Maximilian. ‘al-Ḳādisīya’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 1st ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1913–1938. Vol. 2, 611–613 (DOI 10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_COM_0114). [online]

Streck, Maximilian and Laura Veccia Vaglieri. ‘al-Ḳādisiyya’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 4, 384–387 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0412).

al-Ṭabarī, Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr. The History of al-Ṭabarī. Bibliotheca Persica. Translated from Arabic by Yohanan Friedmann.Vol. 12, The Battle of al-Qādisiyyah and the conquest of Syria and Palestine: A.D. 635–637/A.H. 14–15. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Usher, Sebastian. ‘“Jihad” magazine for women on web’. BBC News Online, 24 August 2004. [online]

Related links

The Worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own (art exhibition by Michael Rakowitz at the Tate Museum)Hā Khūtī: Baʿthist patriotic song praising Ṣaddām and Qādisiyyat-ṢaddāmImage credits

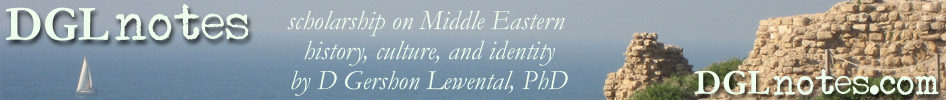

- Depiction of the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah from a copy of the Persian epic Shāh-nāmeh. Source: Wikipedia.

- The Qaws an-Naṣr (‘Victory Arch’), sometimes called the ‘Swords of Qādisiyyah’, commissioned by Ṣaddām to commemorate Iraq’s ‘victory’ in the Iran-Iraq War and opened August 1989. Source: Wikipedia.

- The Qaws an-Naṣr (‘Victory Arch’), sometimes called the ‘Swords of Qādisiyyah’, during a dust storm in 2009. Source: New York Times.

- American soldiers posing in front of the Qaws an-Naṣr (‘Victory Arch’), sometimes called the ‘Swords of Qādisiyyah’, after the 2003 invasion that toppled Ṣaddām. Source: Wikipedia.

- Close-up of the fists in the Qaws an-Naṣr (‘Victory Arch’), sometimes called the ‘Swords of Qādisiyyah’, modelled after Ṣaddām’s own. Source: jamesdale10 (Everystockphoto.com).

- Internet banner for a Sunnī militant group opposed to the Islamic Republic of Iran. Source: Qadesiyoon Media Brigade (website 1) Qadesiyoon Media Brigade (website 2).

- The logo of AlQadisiyya3.com, an anti-Shīʿī website run by a Sunnī cleric in Iraq. Source: AlQadisiyya3.com.

- Front cover of the first issue of the radical Islamist al-Khansāʾ magazine. Source: al-Ghoul.com.