Qādisiyyah in modern Middle Eastern discourse

Overview

Table of contents

3. Appendix: Examples of Qādisiyyah nomenclature

the Saʾad ibn-abi-Waqas of the 1980s(see Makiya, 11).

While the régime in Baghdād most poignantly displayed the use of Qādisiyyah nomenclature in all facets of life, the name has appeared and continues to function in all sorts of guises in the modern Middle East—even reaching Muslim communities outside the region; al-Qādisiyyah graces the names of everything from hotels to ports to military brigades to universities. Even its use as a military symbol predates Ṣaddām, as evident from the existence of a number of al-Qādisiyyah army units, dating back as early as the 1948 War. The trend of memorialising the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah through naming is at least as ancient as the early Tenth Century, when reports mention al-Qādisiyyah Mosque in the city of al-Kūfah. Below, I have divided the types of Qādisiyyah objects into several subjects: (3.1) geography and toponymy; (3.2) state institutions and symbols, and (3.2.1) military forces and installations; (3.3) radical Islamist organisations and institutions; (3.4) culture and the arts, as well as (3.4.1) modern Arabic poetry; (3.5) education, religion, and recreation, and particularly (3.5.1) sporting clubs and teams; and (3.6) miscellanea. These divisions are ranked roughly from the order of greatest state affiliation to least, or in terms of growing individual choice with respect to the decision to select al-Qādisiyyah as a name. Unless otherwise stated, the titles of the following objects and places is ‘al-Qādisiyyah’.

This is a work in progress. Any additions, corrections, and criticisms are most appreciated. Do you have contributions to the appendix of examples of Qādisiyyah nomenclature? Click here.

Note: In order to view items below, click on the headers in order to open a list of examples. JavaScript must be enabled on your web browser.

3.1 Geography and toponymy ► click to expand

Most of these examples were produced by states (particularly Ṣaddām’s Iraq), in order to promote a specific agenda or idea (such as ‘Ṣaddām’s Qādisiyyah’).

3.2 State institutions and symbols ► click to expand

Like the previous section, a common thread linking the following instances of al-Qādisiyyah is that they are state-produced and intended to promote an ideological agenda.

3.3 Radical Islamist organisations and institutions ► click to expand

The appeal to the symbols of early Islam is common also in the rhetoric of a relatively-new player on the scene—radical Islamists—who have sought to use examples from early Islamic history, such as al-Qādisiyyah, to encourage and motivate their members.

3.4 Culture and the arts ► click to expand

Particularly in the case of Ṣaddām’s Iraq, some of the following artistic production is state-produced or inspired; however, some of the examples represent independent, individual choices.

3.5 Education, religion, and recreation ► click to expand

The following examples, from the fields of education, religion, recreation, and sport, represent more a reflection of ‘everyday life’ than the official nomenclature above. Still, some of these next illustrations, such as the names of schools and university, may manifest state-sponsored agendæ.

3.6 Miscellanea ► click to expand

This final category contains examples of Qādisiyyah nomenclature from an assortment of objects, mostly private businesses, which reflect largely the initiative of individuals in the selection of al-Qādisiyyah as their names.

Do you know of other cases of Qādisiyyah nomenclature? If you have any examples to contribute to the lists above, any corrections to point out, or any comments about this appendix, please use this form to suggest submissions.

Bibliography and further reading

Alavi, S M Ziauddin. Arab geography in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Aligarh: Department of Geography, Aligarh Muslim University, 1965.

al-ʿAyyīrī, Shaykh Yūsuf. ‘Shaykh Yusuf Al-Ayiri highlights women’s role in helping, hindering jihad’. Jihadist websites—OSC summary, 04 December 2009.

Baram, Amatzia. Culture, history, and ideology in the formation of Baʿthist Iraq, 1968–69. New York City: St Martin’s Press, 1991.

Bartolʹd, Vasiliĭ Vladimirovich [Wilhelm Barthold]. An Historical geography of Iran, ed. Clifford Edmund Bosworth. Modern classics in Near Eastern studies. Translated from Russian by Svat Soucek. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Bengio, Ofra. Saddam’s word: Political discourse in Iraq. New York City: Oxford University Press, 1998 (DOI 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195114393.001.0001).

Darwish, Mahmoud. ‘My beloved rises from her sleep’. Translated from Arabic by Ben M Bennani. Journal of Arabic Literature 6.1 (1975): 101–106 (DOI 10.1163/157006475X00078).

Davis, Eric M. Memories of state: Politics, history, and collective identity in modern Iraq. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Dawisha, Adeed I. ‘Arabism and Islam in Iraq’s war with Iran’. Middle East Insight 3 (1984): 32–33.

DeYoung, Terri. ‘Nasser and the death of elegy in modern Arabic poetry’. In Tradition and modernity in Arabic literature, ed. Issa J Boullata, Terri DeYoung, and Mounah Abdallah Khouri, 63–86. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Donner, Fred McGraw. The Early Islamic conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. [online (excerpt)]

Donner, Fred McGraw. Narratives of Islamic origins: The Beginnings of Islamic historical writing. Studies in late antiquity and early Islam, 14. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1998.

Gohar, Saddik. ‘The Protest poetry of Muhammad al-Fayturi and Langston Hughes’. Studies in Islam & the Middle East 4.1 (2007): 1–11. [online]

Gieling, Saskia Maria. Religion and war in revolutionary Iran. Library of modern Middle East studies, 18. London/New York City: I B Tauris, 1999.

Halbwachs, Maurice. The Collective memory. Translated from French by Francis J Ditter, Jr and Vida Yazdi Ditter. 1st ed. New York City: Harper & Row, 1980.

Halliday, Fred. Nation and religion in the Middle East. London: Saqi Books, 2000.

Haseeb, Khair el-Din, ed. Arab-Iranian relations. Beirut: Centre for Arab Unity Studies, 1998.

Humphreys, R Stephen. Between memory and desire: The Middle East in a troubled age. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1999.

Jandora, John Walter. The March from Medina: A Revisionist study of the Arab conquests. Clifton, New Jersey: Kingston Press, 1989.

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘A Brief analysis of “Ṣaddām’s Qādisiyyah”’. Online article. DGLnotes.com, 19 July 2012. [online]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Early Islamic history and memory in radical Islamist discourse’. Online article. DGLnotes.com, 12 June 2013. [online]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Qādisiyyah, then and now: A Case study of history and memory, religion, and nationalism in Middle Eastern discourse’. PhD dissertation, Department of Near Eastern & Judaic Studies, Brandeis University, 2011. [abstract]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘“Saddam’s Qadisiyyah”: Religion and history in the service of state ideology in Baʿthi Iraq’. Middle Eastern Studies 50.6 (November 2014), 891–910 (DOI 10.1080/00263206.2013.870899). [online]

Lewis, Bernard. History: Remembered, recovered, invented. New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

Lewis, Bernard. ‘Perceptions musulmanes de l’histoire et de l’historiographie’. In Itinéraires d’Orient: Hommages à Claude Cahen, ed. Raoul Curiel and Rika Gyselen, 77–81. Res Orientales, 6. Bures-sur-Yvette: Groupe pour l’étude de la civilisation du Moyen-Orient, 1994.

Long, Jerry Mark. Saddam’s war of words: Politics, religion, and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. 1st edition. Albany: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Makiya, Kanan. The Monument: Art, vulgarity, and responsibility in Iraq. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1991.

Morony, Michael G. Iraq after the Muslim conquest. 1st ed. 1984. Reprint, Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press, 2005.

Muir, Sir William. Annals of the early Caliphate, from original sources. London: Smith, Edler, & Co., 1883. [online]

Noth, Albrecht, in collaboration with Lawrence Irving Conrad. The Early Arabic historical tradition: A Source-critical study. Studies in late antiquity and early Islam, 3. Translated from German by Michael Bonner. 2nd edition. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1994.

Pourshariati, Parvaneh. Decline and fall of the Sasanian empire: The Sasanian-Parthian confederacy and the Arab conquest of Iran. International Library of Iranian Studies, 10. London/New York City: I B Tauris, 2008 (DOI 10.5040/9780755695270). [online]

Ram, Haggai. Myth and mobilization in revolutionary Iran: The Use of the Friday congregational sermon. Washington: American University Press, 1994.

Rida, Muhammad. ‘Qadisiyya: A New stage in Arab cinema’. Ur 3 (1981): 40–43.

Roy, Marina. ‘Saddam’s arms: Nationalist and Orientalist tendencies in Iraqi monuments’. Public 28 (Winter 2004): 56–76. [online]

Ṣaddām Ḥusayn. ‘President visits scene of grenade incident 2 Apr’. Baghdād, Voice of the Masses in Arabic. 02 April 1980, 1200 GMT. FBIS-MEA-80-066. 03 April 1980, E2–3.

Skarżyńska-Bocheńska, Krystyna. ‘Le reflet de l’Islam dans la poésie tunisienne contemporaine’. Die Welt des Islams 23.1–4 (1984): 182-197 (DOI 10.1163/157006084X00135).

Streck, Maximilian. ‘al-Ḳādisīya’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 1st ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1913–1938. Vol. 2, 611–613 (DOI 10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_COM_0114). [online]

Streck, Maximilian and Laura Veccia Vaglieri. ‘al-Ḳādisiyya’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 4, 384–387 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0412).

al-Ṭabarī, Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr. The History of al-Ṭabarī. Bibliotheca Persica. Translated from Arabic by Yohanan Friedmann.Vol. 12, The Battle of al-Qādisiyyah and the conquest of Syria and Palestine: A.D. 635–637/A.H. 14–15. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Usher, Sebastian. ‘“Jihad” magazine for women on web’. BBC News Online, 24 August 2004. [online]

Related links

The Worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own(art exhibition by Michael Rakowitz at the Tate Museum)

Hā Khūtī: Baʿthist patriotic song praising Ṣaddām and Qādisiyyat-Ṣaddām

Image credits

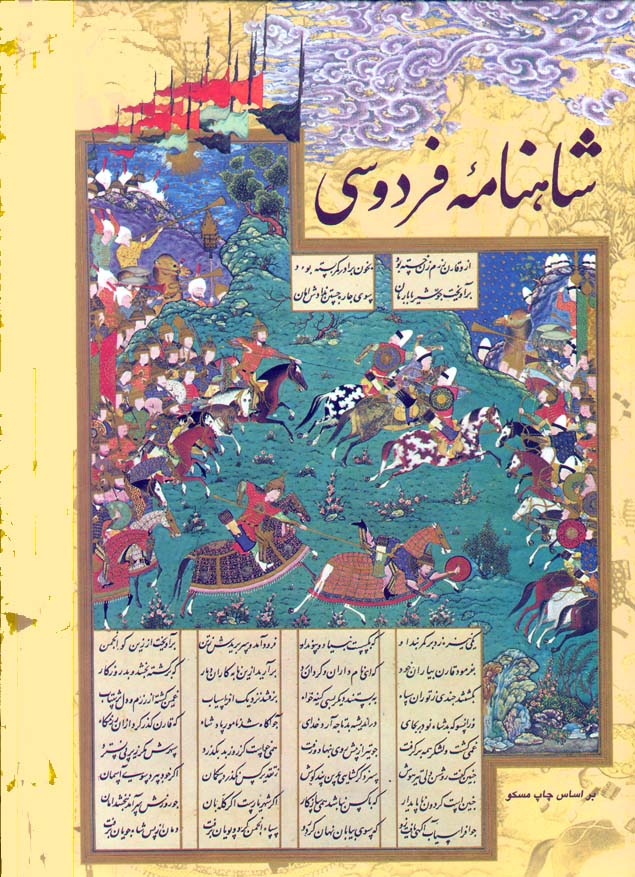

- Depiction of the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah from a copy of the Persian epic Shāh-nāmeh. Source: Wikipedia.

- Stylistic rendering of ‘al-Qādisiyyah’ in Nastaʿlīq script. Source: D Gershon Lewental (DGLnotes).

- Ḥadīthah Dam, initially called al-Qādisiyyah Dam, one of the largest hydro-electric installations in Iraq, build with Soviet and Yugoslav assistance and inaugurated on 28 July 1986. . Source: Wikipedia.

- Iraqi medal issued to commemorate Ṣaddām’s Qādisiyyah. Source: Semoeric website.

- Iraqi medal (

Sword of Qādisiyyat Ṣaddām

) issued to commemorate Ṣaddām’s Qādisiyyah. Source: Internet. - Commemorative (35-fils) stamp issued by Iraq depicting both Battles of al-Qādisiyyah. Source: Wikipedia.

- Iraqi 25-dinar note from the Ṣaddām-era, with the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah depicted on the obverse and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier on the reverse. Source: Wikipedia.

- Iraqi 1-dinar coin from 1980 depicts Ṣaddām in the foreground, with an Arab fighter from the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah in the background. Source: N & N Notaphily & Numismatic’s Munzert.

- Commemorative (100-fils) stamp issued by Iraq in 1981 depicting both Battles of al-Qādisiyyah. Source: eBay.

- al-Qadisiyyah Media Productions, the media and translation arm of a radical Islamic propaganda organisation. Source: JihadMedia.net.

- A logo of al-Qadisiyah TV, a television network affiliated with an Iraqi insurgent group. Source: alQadisiyahTV.com.

- The logo of AlQadisiyya3.com, an anti-Shīʿī website run by a Sunnī cleric in Iraq. Source: AlQadisiyya3.com.

- The logo of Qaadisiya.com, the website of the Somali Islamist group Islamic Courts Union. Source: Qaadisiya.com.

- Logo of Firqat Abnāʾ al-Qādisiyyah (

Sons of al-Qādisiyyah Division

), a Salafī group fighting in the Syrian civil war. Source: Firqat Abnāʾ al-Qādisiyyah (Facebook website). - Internet banner created by the Katāʾib Aḥrār al-Shām (

Freemen of Syria Battalions

), a Salafī group fighting in the Syrian civil war, depicting their cause as a ‘second’ Qādisiyyah. Source: Shabkat al-Jihād al-ʿĀlamī (Network of Global Jihād

). - al-Qādisiyah Palace, designed by TIGRIS Enterprises in Iraq between 1983 and 1993. Source: TIGRIS Enterprises.

- The banner of Ṣaḥīfat al-Qādisiyyah al-Iliktrūniyyah (

The Electronic Qādisiyyah Newspaper

, an online Saʿūdī newspaper. Source: Ṣaḥīfat al-Qādisiyyah al-Iliktrūniyyah (Facebook website). - A Baghdād mural depicting Ṣaddām Ḥusayn surveying both the Seventh-Century and the ‘modern’ Battles of al-Qādisiyyah. Source: unknown; similar image appears in Baram, plate 15.

- Official logo of University of al-Qadisiyah, founded in December 1987. Source: University of al-Qadisiyah (Facebook website).

- The logo of Al Qadesiah Secondary Girls School in Jordan, founded in 2011. Source: Al Qadesiah Secondary Girls School CPSC (Facebook website).

- El Kadisia school (Amsterdam) logo. Source: El Kadisia Islamitische Bredeschool.

- Al Qadeseya Model Independent School (Doha) website banner. Source: Al Qadeseya Model Independent School.

- Qadsia Sporting Club (Kuwait) logo. Source: Qadsia Sporting Club.

- Al Qadisiyah al-Khubar football club (Saʿūdī Arabia) logo. Source: Wikipedia.

- Qādisiyyat-Ṣaddām, a superyacht ordered from a Danish company by Ṣaddām in 1981, equipped with a mosque, missile defence system, and a mini-submarine. Source: Sail-World.com.