Qādisiyyah in modern Middle Eastern discourse

Table of contents

1. The Traditional account

1.1 Buildup to the battle

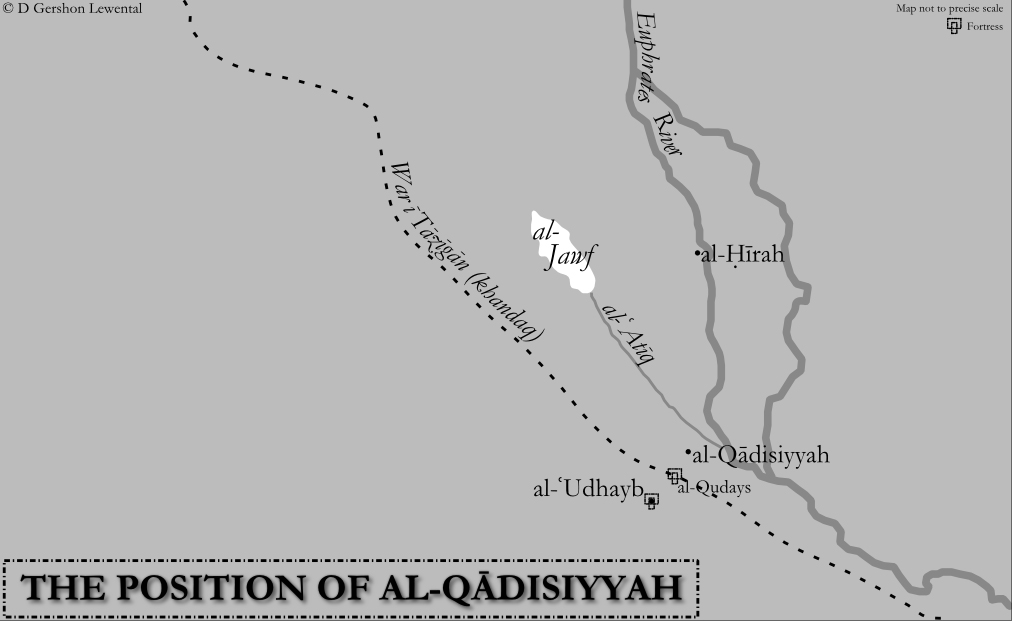

wall of the Arabs (MP War ī Tāzīgān) or the ditch of Shāpūr (Ar. khandaq Sābūr); to their left were sand dunes stretching towards a small lake near present-day Najaf; a thinning extension on the Euphrates River (called al-ʿAtīq) flowed in front of the army, terminating in that lake; and the marshlands of southern Iraq covered the right flank.

At this point, the Muslims sent several envoys to meet with Rostam (and, according to some accounts, with Yazdegerd). These emissaries, notably al-Mughīrah b. Shuʿbah ath-Thaqafī, unnerved the Persian leadership with their shabby and unkempt dress, cavalier and disruptive attitude, and their arrogance and certainty in the strength of their cause. Tearing fine carpets with their swords, piercing cushions and pillows with their spears, and jumping audaciously onto Rostam’s throne, they expressed clearly their rejection of Persian culture and their unwillingness to compromise, despite the generous pecuniary offers to buy them off. Having ominous premonitions, Rostam tried to delay the Battle, but succumbed ultimately to the desire to punish them for their behaviour.

1.2 Arab-Muslim victory and aftermath

The third night, known as the Night of Howling

(Ar. laylat al-harīr), saw the Muslims gaining the advantage and a fierce windstorm that commenced on the fourth morning aided them by blowing sand in the faces of the Persian soldiers. Rostam, who directed the Persian army from atop his throne, took shelter in the shade of a mule after the wind knocked the canopy off of his throne and into the ʿAtīq. An Arab soldier, sometimes claimed to be Hilāl b. Alqamah (or Hilāl b. ʿUllāfah), made his way through the broken Persian lines and chanced upon Rostam, when he swung his sword and knocked a sack off the mule and onto the general’s back. Seeing the throne and noticing the garments worn by the man attempting to flee by swimming across the ʿAtīq, Hilāl recognised him as the famous Rostam. Having caught and beheaded him, he exclaimed: By the Lord of the Kaʿbah!

This news caused the total collapse of the Sāsānian army, elements of which had already commenced retreat. In the mayhem, a group of several thousand soldiers who had chained themselves together drowned in the ʿAtīq, while the Muslims pursued and killed many others; some accepted defeat and Islam.

flag of Kāveh). The Arab fighters became known as the people of al-Qādisiyyah (Ar. ahl al-Qādisiyyah’) and held highest prestige (and pay) of the later Arab settlers within Iraq and one of its important garrison town, al-Kūfah.

According to most accounts, Saʿd and his army pursued immediately the fleeing Persian army up to the outskirts of al-Madāʾin, despatching a few smaller forces who attempted to halt them along the way. After a brief (or long) siege, the Arabs succeeded in penetrating first the western parts of the capital and then the eastern parts, as the royal family and nobility fled eastwards, the Persians relinquishing contrôl over Iraq for good. Thus, the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah broke the power of the Sāsānians, opened the way for the swift Arab-Muslim conquest of the alluvial ‘black’ land of central Iraq (known as the Sawād), and enabled the easy capture of the Sāsānian capital. The Muslims continued their campaign later, defeating two Sāsānian attempts at halting their advance attacks at Jalūlāʾ and at Nehāvand, destroying and supplanting ultimately the Iranian empire.

Bibliography and further reading

Alavi, S M Ziauddin. Arab geography in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Aligarh: Department of Geography, Aligarh Muslim University, 1965.

al-ʿAyyīrī, Shaykh Yūsuf. ‘Shaykh Yusuf Al-Ayiri highlights women’s role in helping, hindering jihad’. Jihadist websites—OSC summary, 04 December 2009.

Baram, Amatzia. Culture, history, and ideology in the formation of Baʿthist Iraq, 1968–69. New York City: St Martin’s Press, 1991.

Bartolʹd, Vasiliĭ Vladimirovich [Wilhelm Barthold]. An Historical geography of Iran, ed. Clifford Edmund Bosworth. Modern classics in Near Eastern studies. Translated from Russian by Svat Soucek. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Bengio, Ofra. Saddam’s word: Political discourse in Iraq. New York City: Oxford University Press, 1998 (DOI 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195114393.001.0001).

Darwish, Mahmoud. ‘My beloved rises from her sleep’. Translated from Arabic by Ben M Bennani. Journal of Arabic Literature 6.1 (1975): 101–106 (DOI 10.1163/157006475X00078).

Davis, Eric M. Memories of state: Politics, history, and collective identity in modern Iraq. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Dawisha, Adeed I. ‘Arabism and Islam in Iraq’s war with Iran’. Middle East Insight 3 (1984): 32–33.

DeYoung, Terri. ‘Nasser and the death of elegy in modern Arabic poetry’. In Tradition and modernity in Arabic literature, ed. Issa J Boullata, Terri DeYoung, and Mounah Abdallah Khouri, 63–86. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Donner, Fred McGraw. The Early Islamic conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. [online (excerpt)]

Donner, Fred McGraw. Narratives of Islamic origins: The Beginnings of Islamic historical writing. Studies in late antiquity and early Islam, 14. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1998.

Gohar, Saddik. ‘The Protest poetry of Muhammad al-Fayturi and Langston Hughes’. Studies in Islam & the Middle East 4.1 (2007): 1–11. [online]

Gieling, Saskia Maria. Religion and war in revolutionary Iran. Library of modern Middle East studies, 18. London/New York City: I B Tauris, 1999.

Halbwachs, Maurice. The Collective memory. Translated from French by Francis J Ditter, Jr and Vida Yazdi Ditter. 1st ed. New York City: Harper & Row, 1980.

Halliday, Fred. Nation and religion in the Middle East. London: Saqi Books, 2000.

Haseeb, Khair el-Din, ed. Arab-Iranian relations. Beirut: Centre for Arab Unity Studies, 1998.

Humphreys, R Stephen. Between memory and desire: The Middle East in a troubled age. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1999.

Jandora, John Walter. The March from Medina: A Revisionist study of the Arab conquests. Clifton, New Jersey: Kingston Press, 1989.

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘A Brief analysis of “Ṣaddām’s Qādisiyyah”’. Online article. DGLnotes.com, 19 July 2012. [online]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Early Islamic history and memory in radical Islamist discourse’. Online article. DGLnotes.com, 12 June 2013. [online]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘Qādisiyyah, then and now: A Case study of history and memory, religion, and nationalism in Middle Eastern discourse’. PhD dissertation, Department of Near Eastern & Judaic Studies, Brandeis University, 2011. [abstract]

Lewental, D Gershon. ‘“Saddam’s Qadisiyyah”: Religion and history in the service of state ideology in Baʿthi Iraq’. Middle Eastern Studies 50.6 (November 2014), 891–910 (DOI 10.1080/00263206.2013.870899). [online]

Lewis, Bernard. History: Remembered, recovered, invented. New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

Lewis, Bernard. ‘Perceptions musulmanes de l’histoire et de l’historiographie’. In Itinéraires d’Orient: Hommages à Claude Cahen, ed. Raoul Curiel and Rika Gyselen, 77–81. Res Orientales, 6. Bures-sur-Yvette: Groupe pour l’étude de la civilisation du Moyen-Orient, 1994.

Long, Jerry Mark. Saddam’s war of words: Politics, religion, and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. 1st edition. Albany: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Makiya, Kanan. The Monument: Art, vulgarity, and responsibility in Iraq. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1991.

Morony, Michael G. Iraq after the Muslim conquest. 1st ed. 1984. Reprint, Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press, 2005.

Muir, Sir William. Annals of the early Caliphate, from original sources. London: Smith, Edler, & Co., 1883. [online]

Noth, Albrecht, in collaboration with Lawrence Irving Conrad. The Early Arabic historical tradition: A Source-critical study. Studies in late antiquity and early Islam, 3. Translated from German by Michael Bonner. 2nd edition. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1994.

Pourshariati, Parvaneh. Decline and fall of the Sasanian empire: The Sasanian-Parthian confederacy and the Arab conquest of Iran. International Library of Iranian Studies, 10. London/New York City: I B Tauris, 2008 (DOI 10.5040/9780755695270). [online]

Ram, Haggai. Myth and mobilization in revolutionary Iran: The Use of the Friday congregational sermon. Washington: American University Press, 1994.

Rida, Muhammad. ‘Qadisiyya: A New stage in Arab cinema’. Ur 3 (1981): 40–43.

Roy, Marina. ‘Saddam’s arms: Nationalist and Orientalist tendencies in Iraqi monuments’. Public 28 (Winter 2004): 56–76. [online]

Ṣaddām Ḥusayn. ‘President visits scene of grenade incident 2 Apr’. Baghdād, Voice of the Masses in Arabic. 02 April 1980, 1200 GMT. FBIS-MEA-80-066. 03 April 1980, E2–3.

Skarżyńska-Bocheńska, Krystyna. ‘Le reflet de l’Islam dans la poésie tunisienne contemporaine’. Die Welt des Islams 23.1–4 (1984): 182-197 (DOI 10.1163/157006084X00135).

Streck, Maximilian. ‘al-Ḳādisīya’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 1st ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1913–1938. Vol. 2, 611–613 (DOI 10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_COM_0114). [online]

Streck, Maximilian and Laura Veccia Vaglieri. ‘al-Ḳādisiyya’. In Encyclopædia of Islam. 2nd ed. Leiden: E J Brill, 1960–2005. Vol. 4, 384–387 (DOI 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0412).

al-Ṭabarī, Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr. The History of al-Ṭabarī. Bibliotheca Persica. Translated from Arabic by Yohanan Friedmann.Vol. 12, The Battle of al-Qādisiyyah and the conquest of Syria and Palestine: A.D. 635–637/A.H. 14–15. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Usher, Sebastian. ‘“Jihad” magazine for women on web’. BBC News Online, 24 August 2004. [online]

Related links

The Worst condition is to pass under a sword which is not one’s own (art exhibition by Michael Rakowitz at the Tate Museum)Hā Khūtī: Baʿthist patriotic song praising Ṣaddām and Qādisiyyat-ṢaddāmImage credits

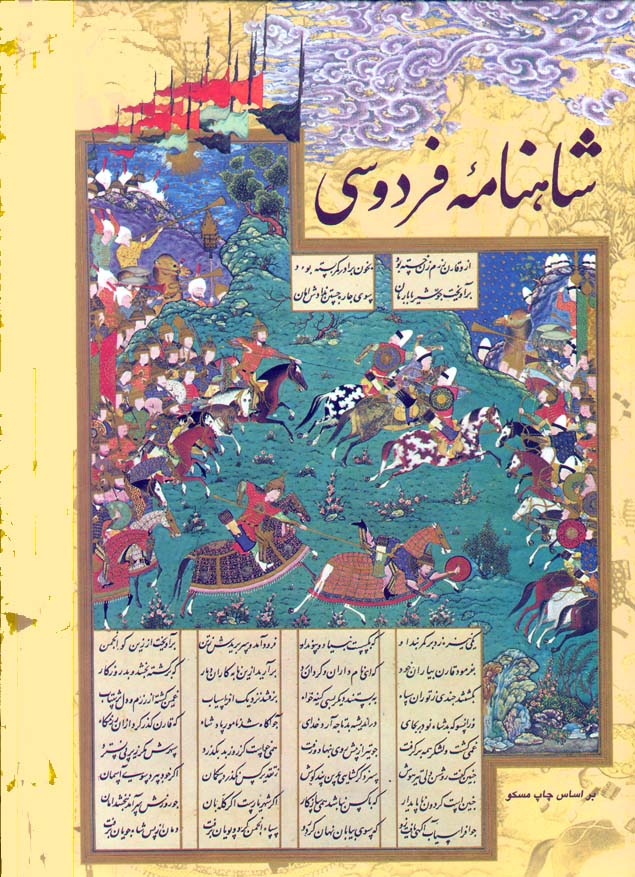

- Depiction of the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah from a manuscript of the Persian epic Shāh-nāmeh. Source: Wikipedia.

- Ruins of the royal palace (Ayvān-e Khosrow) in Madāʾin (Ctesiphon), the Sāsānian capital. Source: Wikipedia.

- Map of the strategic position of al-Qādisiyyah. Source: D Gershon Lewental (DGLnotes).

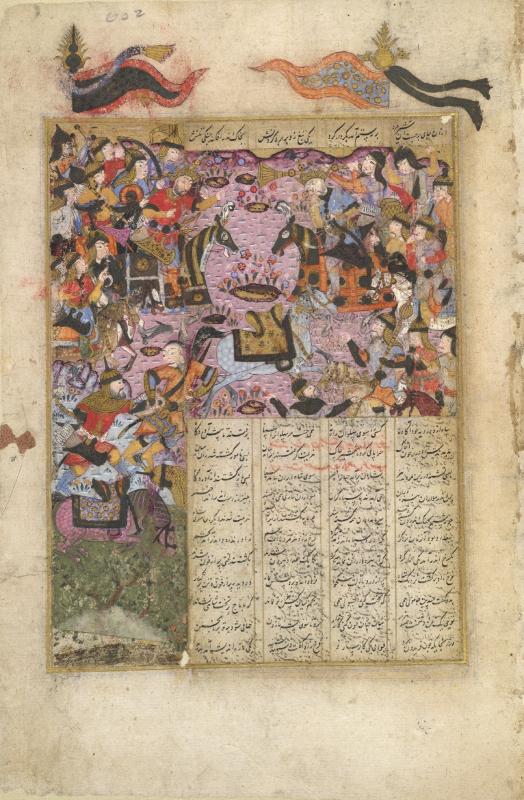

- Depiction of the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah from a manuscript of the Persian epic Shāh-nāmeh. Source: British Library (MS. I.O.Islamic 3265 (1614) f. 602r).

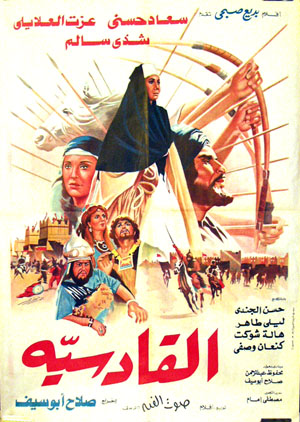

- Poster for the Egyptian film al-Qādisiyyah (1981). Source: MusicMan.com.